For my blog

post this week, I wanted to use this opportunity to continue with a project I

began last semester in my Los Angeles cinema class and that I will be

presenting at PCA this coming April as many of the topics from this week’s

reading relate to my research. In particular I would like to focus on the

practice of consumerism in suburban families and the ways in which television

functions in establishing the “other” in relation to mainstream society. I will

be focusing on George Lipsitz’s article, “The Meaning of Memory: Family, Class,

and Ethnicity in Early Network Television Programs” in order to examine the

social construction of suburbia through the coming-of age narrative in the Fox

television series The O.C.. I know my

ideas are not fully flushed out just yet, but I thought this would be a good

excuse to rethink some of my earlier thoughts from a TV Theory

perspective.

---------

As Lipsitz

says in his article, the popularity of the ethnic, working class sit-coms of

the late 1940s and 1950s was quite unusual based on the commercial funded

network programming in place (71). Because a mass audience was required in

order for networks to attract the necessary advertisers to pay for the

programming and make a profit themselves, the programs produced at this time

worked to encourage a “depiction of homogenized mass society, not the

particularities and peculiarities of working-class communities” (Lipsitz

71-72). This tradition carries on through to today, in which the majority of

television features middle- or upper middle-class individuals and families,

because these are the types of families to which the television producers

believe the largest number of viewers will relate. Because the TV family is in

many ways similar to the real-life American family, this resemblance between

television family life and family relations resemble life and relations in real

families allows for “television families often comprise the lexicon used to

discuss real families” as well as being

“frequently seen to narrate, or even cause, changes in real family

life” (Douglas, 164). While it is

recognized that Cohens and Coopers of The

O.C. are not factual representations of family life, these characters can

be used as a method of examining the ways in which television families are now

portrayed as well as granting us new insights into our understanding of what

growing-up and living in suburbia holds. As Lipsitz claims, it was this connection

to the television characters through real life, identifiable issues- albeit in

“truncated and idealize” forms- that allowed the audience to sympathize with

these characters and the networks to maintain their large viewing numbers

(86-87). I would argue that in the same ways the working-class, ethnic sit-coms

of the 50s were able to negotiate the unattractive aspects of the working class

characters, the upper-class character in The

O.C. were handled in a similar way. In fact, more than anything these

characters presented the ultimate aspirational lifestyle for viewers.

While many

associate the rise of consumerism with mass production during the industrial

revolution, this trend can be traced back to more recent developments following

the years of sacrifice following the Great Depression and the two World Wars.

One major source of this new consumer attitude arose based on the increasingly

widespread acceptance of television with it’s heavily pro-consumption content.

For the first time in American history, instead of comparing “one’s life to

neighbors, coworkers and friends, television characters and lifestyles became

the new benchmark for consumerist goals” (Bindig and Bergstrom,

87). As Lipsitz explains in his article, television of the 50s functioned as a

tool used for the legitimation of emerging consumer lifestyles (75). By seeing

relatable characters on television acquire and benefit from a vast number of

consumer products, viewers in turn would come to accept the new consumerist

lifestyle of the post-war era and turn away from the frugal traditions of the

past (75). In the upper class Newport Beach of The O.C., consumerism is ever present and completely engrained

within the lives of all the characters. This trait is brought to light when

Seth comments in the pilot, “Why do they even need a fashion show?

Everyday is a fashion show for these people.” And keeping up with the latest

trends and designers can be a lot of pressure for these young characters.

According to a 2007 study by Molnar and Boninger, teens represent one of the

largest consumer demographics, making up approximately $200 billion in spending

power, which also means these young adults feel the effects of consumerism more

directly (Bindig and Bergstrom, 87). In addition to the financial burden of

consumer culture, it has been shown that these kinds of consumerist mentalities

can often negatively impact the “physical, mental, social, and emotional health

of youth” (Bindig and Bergstrom, 88).

During the

Christmukkah episode (S1, E13) Marissa tells Ryan how the mall makes her feel

like everything is going to be all right. She calls it perfect and says, “You

walk out feeling like all your troubles can be solved by the right nail polish

or a new pair of shoes.” However, her troubles are just beginning because after

the fallout of her father’s embezzling scandal, Marissa can no longer afford

the trappings of her former life. This since of loss pushes Marissa to shoplift

several items from the mall. The effect of all this consumerism on the

characters is especially apparent among the female characters of the show. For

Julie Cooper life has always been about keeping up appearances. In her Juicy

Couture track-suits and manicured nails, Julie is the self-proclaimed “Queen of

the Nupesies.” Julie’s and her family’s consumerism and constant spending are

the primary reasons that pushed Jimmy to embezzle money from his clients’ hedge

funds. It was important to the Cooper family to keep up the appearance of

wealth, even when they were left with almost nothing. Julie would often name

drop designers and tell Marissa what to wear or how to do her hair, thus

pushing her own consumerist ideas onto her daughter. Julie’s behaviors are very

similar to many of the original critiques of suburban living. It was perceived

that “suburbanites drank too much and were too hungry for status. They ruined

their own lives, then forced their children into the same competitive mold”

(Marsh and Kaplan, 43). Keeping up appearances is important in this

environment. As long as the teens were able to maintain the façade of

togetherness, then the parents leave them for the most part to do as they

please.

Throughout

the series, The O.C. continually

perpetuates the idea that working class individuals are in some way more likely

to fall into criminal patterns of behaviour. By continually reinforcing this

connection, the show is in many ways suggesting that crime is inescapable for

children growing up in this environment (Binding and Bergstrom, 50). For the

character of Ryan Attwood, his broken home life is often taken as one of the

reasons surrounding his sometimes-violent outbursts. In addition to having an

absent and incarcerated father, Ryan’s older brother, Trey, also serves as a

bad influence on his younger brother. Surrounded as Ryan is by these criminal

male role models and with an “addiction-addled mother who fails to intervene in

any substantive way, the criminality of Ryan’s working-class family appears to

be pathological and dysfunctional” and the characters in the series see these

as valid reasons for Ryan’s anger and violent reactions (Binding and Bergstrom, 50). However, in The O.C. crime does not disappear once

you enter the affluent, suburban safe-haven of Newport Beach, the crime just

changes. Where Ryan and his biological brother, Trey, were arrested for sealing

a car, Jimmy Cooper was caught embezzling money from his client’s hedge funds.

Newport Beach is therefore not devoid of crime, it’s criminals are just more

“white-collar” criminals like Jimmy Cooper or the crime is masked, like in the

case of real estate mogul and Kirsten Cohen’s father, Caleb Nichol, who uses

backroom deals and extortion to build his real estate empire. Therefore, it is

no surprise that both of these characters are wealthy and white because

according to bell hooks, “class and race are intertwined, and analyzing how the

institutional structures benefit the white-supremacist capitalist patriarchy”

leads us to an understanding of how crime is perceived and represented among

these differing communities and perpetrators (Binding and Bergstrom, 47). In

the case of Ryan and Trey, the series portrays crime as being all around them

and therefore their involvement is not unusual. In the cases of Jimmy and

Caleb, their criminal acts are often interpreted as singularities within the

community and are always justified by each man repeatedly saying they committed

their various crimes in order to better provide for their families.

It should

also be noted that ethnic minorities are for the most part not shown in

The O.C., which is more than can be said

regarding working class individuals who are largely portrayed in a negative

light. Where you do see more diversity is only when you venture inland from the

coast from Newport Beach. According to urban studies scholars, Mary Brooks and

Paul Davidoff, from the earliest development of suburbs this separation along

racial and economic lines has always existed within suburban environments. For

Brooks and Davidoff, the creation of protected or defended suburbs has been one

of the methods employed to separate rich communities from poor, “to protect

rich Americans and their children from contact with poor and even middle-class

Americans and their children, and to separate black Americans from white

Americans. From an urban nation we have become predominantly a suburban one,

and this shift of population and of lifestyle has helped to sharpen the race

and class cleavages among us” (Davidoff and Brooks, 137). This separation

applies to the teenage characters represented on

The O.C. as well.

In general,

lower class teens are not portrayed

as multi-dimensional characters and are instead confined to the neoliberal

representations of race, crime, and poverty demonstrated on the show. For

example, the Hispanic character of Eddie who appears in the first season was

originally depicted as someone who was “making it” in Chino. He had a steady

job, an apartment, and was not caught up in criminal activity unlike many of

his peers. However, it was later reveled that Eddie was abusive to his

girlfriend, Theresa. While Eddie initially seems to subvert the cultural norms

placed on him based on his race and social standing, eventually he conformed. “By

depicting the working class [and ethnic minorities] as more dysfunctional than

the upper class, the media are subtly suggesting that there are individual

reasons for their economic situation rather than structural ones” which further

sets the white, wealthy, characters apart from the rest of society-sequestered

away from the riff-raff in their gated communities (Bindig and

Bergstrom, 51). All of these

things continually reinforce the neoliberal slant of the show meaning that by

repeatedly representing crime to be linked to the working class, The O.C. consistently reinforces the notion that the inherent dysfunction

of the working class is in some way a cause of their own unhappiness (Binding and Bergstrom, 51). Upon

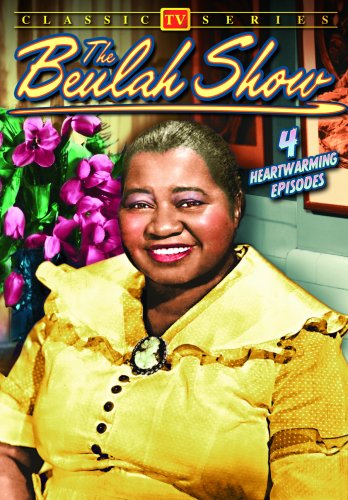

reading Lipsitz’s account of working-class, ethnic minorities in shows such as Amos ‘n’ Andy, it appears as if The O.C. does not fall in the same

category. According to Lipsitz, “the working class depicted in urban, ethnic

working class situation comedies of the 1950s bore only a superficial

resemblance to the historical American working class” (92). In this way, ethnic

minorities and the working class were presented as a ‘made for TV” version of

their true representations. This makes me wonder what exactly caused this shift

in television’s representation of these groups and what we can learn from this

ever-changing perception?

Well, that’s all I have for now. Thanks for reading all my ramblings

and if you have any thoughts or suggestions I would love to hear them because as

I mentioned this is a work in progress for PCA coming up in a few months.